Although many of the posts in this blog see me banging on about the manifold woes of cycling around a big, dirty, car-clogged city, by far my favourite flavour of bicycling is cycle touring – lobbing a load of stuff on to the bike and sodding off to some wilderness or other.

Last year we did the Peak District in the spring, Berlin to Copenhagen in the summer, and Wales (including a gear run-down) later in the year.

This year I suggested to my cycle touring group – the Pootlers’ Touring Club – that we plan and execute probably the most remote bike tour in the UK: the Hebridean Way (or Sustrans Route 780), a cycle route along the length of the Outer Hebrides. This is one I’ve had my eye on for a few years but was always deterred by the inordinate faff of getting there and back (on which more anon). Realising that the level of faff is not likely to recede any time soon, we set about overcoming this logistical challenge.

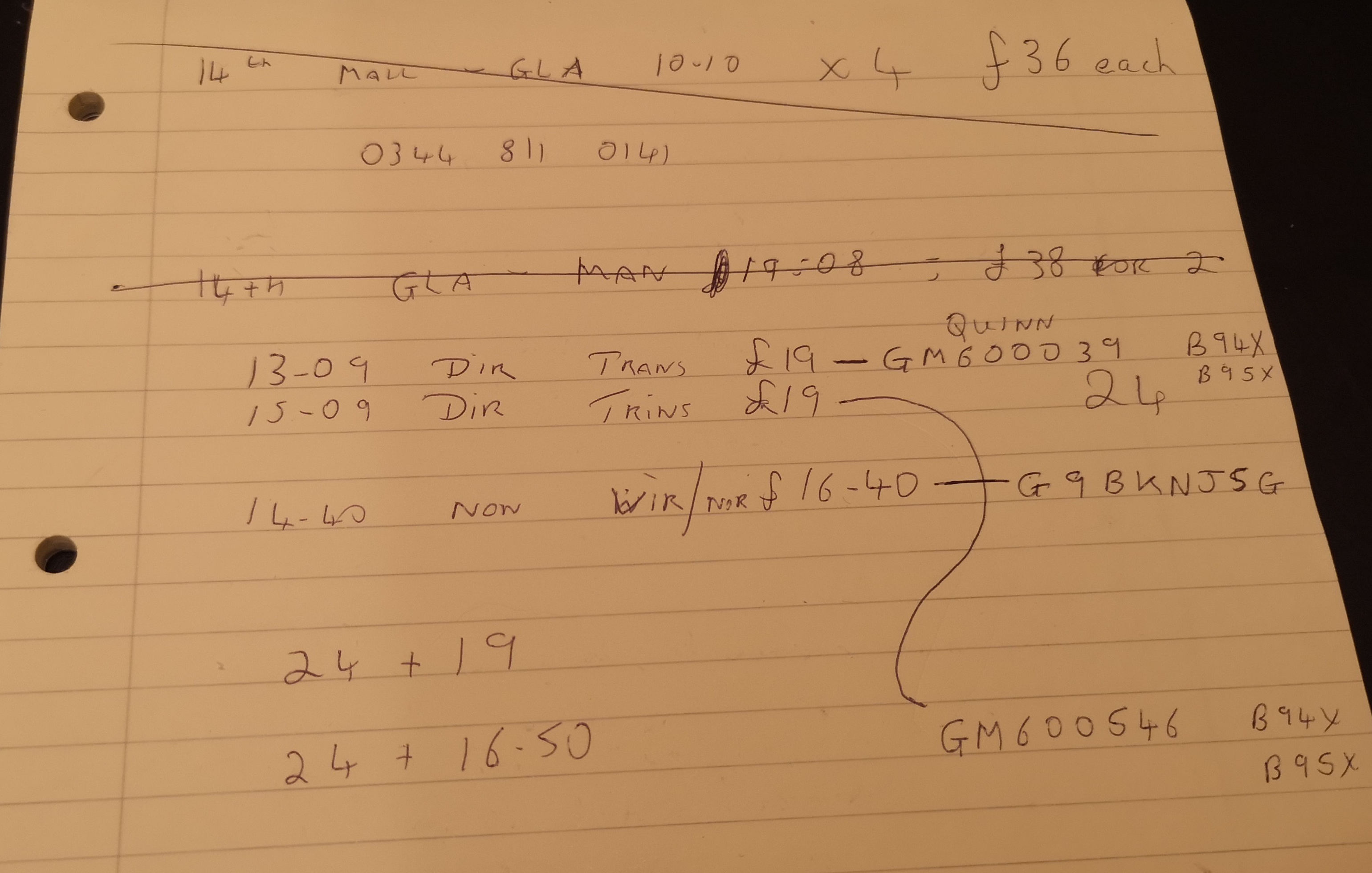

Booking five people with bikes on four separate train routes can be a laborious process in this country. It took us two one-hour intensive phone sessions to get all the reservations in place.

How long to plan for

One piece of advice we were given, and absolutely endorse, is to give yourself longer for this ride than you otherwise might for a tour of this length. Indeed, at around 180 miles, this route is equivalent to popular coast-to-coast rides such as the C2C or the Way of the Roses, which many competent riders will tackle in a long weekend or less.

The Hebridean Way, however, is a different proposition. Ferries, weather, scarcity of accommodation and shops are all factors that add a little extra difficulty, so we opted for a total trip time of twelve days, including three travelling days and a few days on the Isle of Skye on the way back. The trip was duly arranged for Thursday 2 to Tuesday 14 May. All we planned in advance was the travel and the first and last night’s accommodation. Everything else was to be decided on the fly, which I find a rather splendid way of travelling.

What we took

The short answer is, as ever, too much! However, it’s really difficult to know exactly what you’re going to need in a place where conditions are as capricious as in the Hebrides. At the very minimum I had:

- 2-3 days’ cycling clothes, plus waterproofs, arm/leg warmers, gloves, caps

- 2 changes of clothes for off the bike plus quilted jacket & waterproof trail shoes & flip flops

- Tent, sleeping bag, mat, ultralight camping chair

- Camping stove, pots & cutlery, gas

- Food for 3-4 days – freeze-dried meals, tinned beans/fish, packet rice etc.

- Bike tools and spares

- Phone, power banks, Beeline navigation device

- Toiletries, suncream, insect repellent, beard oil

Even though we all really tried to limit what we were carrying, we still all ended up with gross weights of luggage + bike of around the 40kg mark – because we needed to be prepared for all eventualities.

Erik the Red fully loaded and ready to go.

Getting there

The problem with the Outer Hebrides is precisely what makes them so appealing: they’re so ruddy far away. Indeed, you could fly to pretty much any destination in the world in the time it took us to get from Manchester to the start of the route at Vatersay. But that’s part of the fun of this trip. This is how we did it:

Leg 1: Manchester to Glasgow

Because the main rail companies that operate in England only take two bikes per train, we had to split our group of five pootlers across three trains. One went up a day earlier, and the remaining four arrived in Glasgow via two separate trains, two hours apart, on the Thursday afternoon.

Two’s your lot for bikes on most English trains.

Leg 2: Glasgow to Oban

Coalescing in Glasgow, the four of us were able to take the same train out to Oban the same afternoon, because Scotrail helpfully permit six bicycles per train, pretty much in the same space that less arsed train companies grudgingly allow for two.

Scotrail’s bike section carries six bikes per train, suspended on hooks by the back wheel.

Night 1: Oban Backpackers hostel

There is one ferry a day from Oban to Castlebay on Barra, where we needed to get to to start the ride. The ferry departs around lunchtime. There is no train from Manchester that will get you into Oban in time for the ferry, so an overnight stop somewhere is inevitable.

We opted for the Oban Backpackers hostel and booked out a six-person dorm for the five of us, which was perfectly comfortable for one night. If you’ve never been, Oban is a lovely little Scottish port town, albeit severely traffic-choked.

Oban by night.

Leg 3: Oban-Castlebay

After a morning pottering around Oban securing last-minute supplies, we boarded the ferry just after noon and settled down for the five-hour crossing. Yes, you did read that right. And yes, that’s how far away this place is. See what I mean?

Bikes ready for boarding.

Leg 4: Castlebay-Vatersay

On arriving at Castlebay, it was around a 5-mile ride across the causeway to Vatersay, where the Hebridean Way officially starts. Given it was already early evening, we picked up provisions from the Coop at Castlebay, pitched camp by the start-of-route sign, cooked a campsite meal and retired early, ready to push off the next morning.

And that’s how it takes two days to get to the start of this ride.

Campsite cooking: veggie sausages and spicy rice washed down with pink G&T. Living it up!

The weather

Scottish weather is notoriously unpredictable, and this is doubly so at its outer reaches. Within the first 20 minutes of arriving in Castlebay, we experienced rain, hail, sunshine and wind, the latter becoming very much a constant, contrary companion throughout the whole ride. Usually, the Outer Hebrides enjoy southerly winds, which give the intrepid bike tourist a welcome push if they ride in the advised direction from south to north. Sadly for us, as of a couple of days before we arrived, the UK had been in the grip of a minor yet unseasonable cold snap due to a 180-degree shift in wind direction, and it was into these stiff northerlies that we pedalled our over-laden bikes.

The winds also added an extra few degrees of chill to the feels-like temperature, and we all struggled to keep warm at various points in the trip: despite our cautious preparations, none of us had quite anticipated that we’d need full-on winter gear for a holiday in the UK in May.

One thing we were mercifully spared was rain, which could have made the trip quite miserable indeed. As it was the clear, cold air permitted stunning views and amazing photographs, which will far outlast the memory of the chill in our bones.

If you didn’t know otherwise, this might be a Caribbean beach. However, with a feels-like temperature of around 2 degrees, there’s a reason it’s so empty…

The terrain and other practicalities

The Outer Hebrides aren’t particularly hilly – the biggest climbs are the stunning mountain passes either side of Tarbert, but riding here poses its own challenges. Again I’ll mention the winds, which add a crazy level of difficulty if they’re coming from the wrong direction. Our hardest day was cycling from Howmore to Ravenspoint – just 48 miles with around 3,200 feet of climbing – and we were wiped out when we arrived. At home that’d be a nice morning pootle. So another benefit of giving ourselves plenty of time was that we were able to take a rest day when we felt we needed it, which we did around half-way in.

The route also involves two internal ferry crossings: one from Barra to Eriskay, the other from Berneray (North Uist) to Leverburgh (Harris). Both of these needed researching in advance – the Barra ferry doesn’t sail on Sundays, so we had to be sure to be off Barra on the Saturday or we’d have been stranded. The Berneray ferry, for its part, was on a special tidal timetable when we sailed, meaning it set off a good hour before the published time, so it certainly makes sense to check the Calmac service changes page before heading off for the ferry.

Shops, pubs and eateries can pose challenges, too, in that they are very few and mostly far between. You really can’t rely on happening across somewhere when you’re feeling peckish, so you need to make sure you have enough food for the day or plan your stops carefully based on up-to-date information (we found pooling the knowledge of Google and locals we happened across at our accommodation was the most accurate method).

However, there are some real gastronomic surprises there. Check out the menu at the shack at the Berneray ferry jetty – which wouldn’t be out of place in the most hipsterified Northern Quarter independent coffee shop:

Or, even more startling, this amazing offering in a wooden cabin at Callanish on Lewis. I thought my dream of veggie haggis had died as we left Oban empty-handed, but these guys came to the rescue. Amazing!

Where to stay

You’re allowed to wild-camp in Scotland, which sounds totally romantic – arrive somewhere, put up your tent, cook your dinner and have a cold beer in the midst of the most amazing scenery. At the same time, the stark realisation as to what the lack of any sanitary facilities whatsoever actually meant somewhat took the edge off the romance. Added to that was the ever-present cold and wind, and over the whole trip we only semi-wild-camped once – outside the community café on Vatersay, which has 24-hour toilet and shower facilities.

Having tents and camping gear did, however, give us options: we knew we’d have somewhere to stay every night, even if it did mean a potentially uncomfortable doze in a tent. The weather being as it was, however, we kept the camping to a minimum. Had it been ten degrees warmer, as it it ought to have been at this time of year, it would have been a different story.

A rather strange phenomenon on the Outer Hebrides is the handful of Gatliff Trust hostels. Unlike hostels I’ve experienced anywhere else, you can’t book them. Instead, they work on a “bagsy” system: you turn up, walk into the dorm room and if you see an empty bed, you put your stuff on it and bagsy it. The warden will appear at some point and collect the fee, and you cook your dinner in the communal kitchen whilst mingling with (or perhaps attempting to avoid) the other guests.

Other, more conventional hostels (such as there were any) were easy enough to book a day or two in advance at this time of year, and campsites of course simply let you turn up, pitch up and bed down.

The Gatliff Trust hostel at Berneray.

Crime

There is no crime on the Outer Hebrides. We got very used to leaning our bikes somewhere and knowing they’d be fine for however long we’d be away, which is a very pleasant way to live.

The people

The people of the Outer Hebrides are some of the friendliest I’ve ever encountered. I guess this is a result of the harsh environment they inhabit, knowing how easy it is to find oneself in need of a favour. A few examples:

- The warden at Ravenspoint hostel who, despite officially having finished work over an hour previously, re-opened the shop so we could stock up on supplies for tea and breakfast.

- The owner of the campsite in the remote hamlet of Shawbost who, in response to our question, “is there a shop nearby where we can buy beer?” replied, “no, but my husband is in Stornoway today, so tell me what you’d like and I’ll get him to pick it up for you.” Which he duly did, and repeated the favour the next day without being asked. What a star!

- The ladies of the community hall in Balallan. It had just started to rain heavily and we were looking for shelter, so we stopped at this building that had a sign for a tearoom. We were told that the tearoom was closed as they were currently hiring staff, but we could shelter in the local museum room. After around 20 minutes they brewed up for us anyway, so we ended up with an unexpected, informal tearoom experience after all. Such kindness!

Impromptu brew in Balallan.

Getting back

The Hebridean Way is a point-to-point route as opposed to a circular one, meaning that whatever challenges you overcame to get to the start, there are different ones for getting home. What’s more, the finish point of the Hebridean Way is the Butt of Lewis – literally an outcrop of rock in the Atlantic Ocean – so you can’t just get a train or boat or whatever as soon as you complete the ride. The most obvious option is to pedal down to Stornoway (ringed red on the below map), get the ferry to Ullapool on the mainland, cycle across Scotland on the A835, which looks like a dirty great A road, and catch a train home from Inverness. Which sounds expedient yet somehow unappealing.

Given we’d allowed ourselves a decent chunk of time for this trip, we decided to tag on a long outro and instead headed back to Tarbert (ringed below in orange) and caught a ferry to the Isle of Skye, which ultimately proved to be the right choice for us.

Options for getting off the Outer Hebrides: Stornoway in red or Tarbert in orange.

The Isle of Skye

I love the Isle of Skye. I’ve been twice before – once as a hiker, the second time as lone cycle tourist – and it’s one of those places I can’t imagine ever tiring of. And this third time was no exception. The moment we wheeled our bikes off the ferry at Uig, the whole group fell under Skye’s spell. The sun was warmer, the wind milder and the birds more playful as we rolled the few miles from Uig down to Portree. There, after the sparseness of the Outer Hebrides, we took full advantage of the hostelries clustered round the main square and tumbled into bed well after midnight, our latest and drunkest night of the whole tour.

Ferry docked at Uig, Isle of Skye.

Slightly worse for wear the next day, we had an easy, scenic ride to Broadford via Sligachan, and the final day saw us trundle to Armadale to catch the ferry, stopping for a tour of the Torabhaig distillery on the way.

A final night in a rather institutional hostel in Mallaig, early Scotrail service back to Glasgow and the two-per-train game home to Manchester, and the tour was at an end.

Final group shot of the trip. End of this tour, but where will we go next?

Verdict

The Hebridean Way was everything I’d hoped for and more. In my modest experience it’s certainly been the most demanding cycle tour for all the reasons described above, but that’s what you come for: the remoteness, the views, the physical challenge, coping with the weather, the sheer joy of a riding a bicycle every day for over a week, the companionship and camaraderie of the amazing group of people I managed to convince to come with me and ride bikes at the very edge of the British Isles. It wasn’t always easy, but I loved every moment.

I would definitely recommend the route to anyone with a bit of serious riding under their belt who enjoys remoteness and a bit of a challenge. However, because it’s such a pain to get to, do give yourself enough time to savour the ride as opposed to blasting through it in two or three days (as one group of true MAMILs we met in Tarbert were doing). As one member of our group was wont to say, this is definitely the trip of a lifetime.

Any questions or comments, please fire away. Otherwise I hope this has been useful for some background info on the route, and also that you’re feeling inspired to get out there and do the next multi-day cycle ride of your own.

We also made a video of the trip, which you can watch here:

Great video Nick,

I am doing the same trip as we speak in Tarbert at moment, what an amazing trip

Cheers

Mark Riley

Good write up – we did the trip the week after you and had great weather (sorry ..). We travelled light (superlight compared to you guys) and stayed in hostels. Having driven to Oban we had to get back there so we hoped off Skye to Mull and back that way to pick up the car in Oban. It is a fab area and as you way, well worth taking your time. I would love to go back and just explore more ..

Great blog and very well written and constructed. The video was a nice touch too. Your tales oft kindness of locals was reflected in our own trip, about a week after yours and like Martine said above, in improving weather, cold start but getting up above 20° – I know! I realise this sounds an alien concept to cyclists but we seemed to have tailwinds for the first four days. When we had a headwind on the return, it was very tough, so I feel your pain!

Interesting that you were so captivated by Skye, as we thought that was a bit of a letdown compared to the Hebs, since it seemed chock full of cars and on busier roads. The scenery there is amazing, no doubt,, different to anywhere else in Britain, albeit the greyer weather we faced on Skye reduced the magic of the island. I know you guys travelled “heavy” with camping gear, and so had the surety of a bed every night, but we found it was probably essential to book accom way in advance if not camping.

Good effort in getting there by train too, I imagine that took some doing with our prehistoric public transport system.

Nice blog, I’ll keep my eyes open for future posts.

Well done guys.

I’m planning this trip in a few weeks and to help me out would you have a copy of the GPX file of the route, especially the sky part